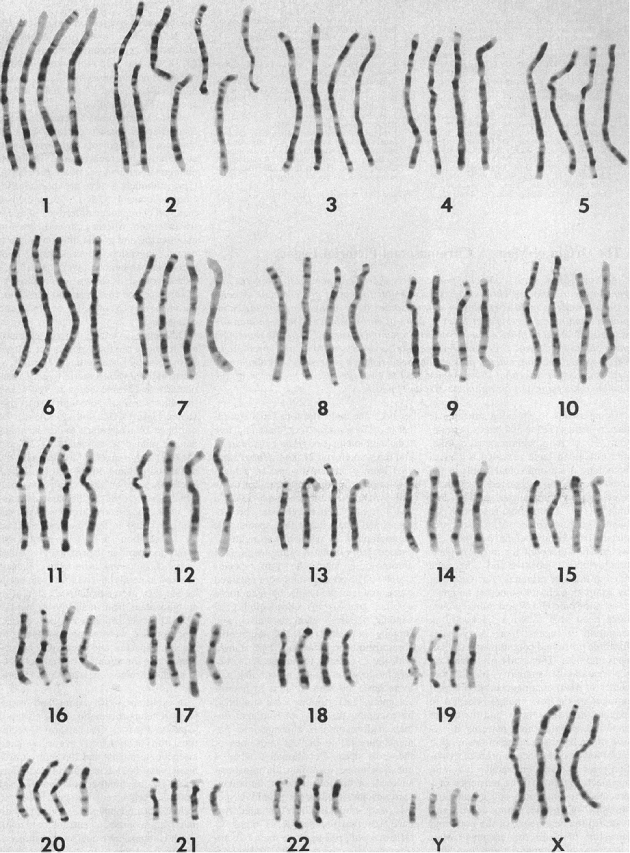

The story is captivating and frequently told in biology textbooks and popular science: humans possess 46 chromosomes while our alleged closest relatives, chimpanzees and other great apes, have 48. The difference, evolutionists claim, is due to a dramatic event in our shared ancestry – the fusion of two smaller ape chromosomes to form the large human Chromosome 2. This “fusion hypothesis” is often presented as slam-dunk evidence for human evolution from ape-like ancestors. But when we move beyond the narrative and scrutinize the actual genetic data, does the evidence hold up? A closer look suggests the case for fusion is far from conclusive, perhaps even bordering on evidence conjured “out of thin air.”

The fusion model makes specific predictions about what we should find at the junction point on Chromosome 2. If two chromosomes, capped by protective telomere sequences, fused end-to-end, we’d expect to see a characteristic signature: the telomere sequence from one chromosome (repeats of TTAGGG) joined head-to-head with the inverted telomere sequence from the other (repeats of CCCTAA). These telomeric repeats typically number in the thousands at chromosome ends.

The Missing Telomere Signature

When scientists first looked at the proposed fusion region (locus 2q13), they did find some sequences resembling telomere repeats (IJdo et al., 1991). This was hailed as confirmation. However, the reality is much less convincing than proponents suggest.

Instead of thousands of ordered repeats forming a clear TTAGGG…CCCTAA structure, the site contains only about 150 highly degraded, degenerate telomere-like sequences scattered within an ~800 base pair region. Searching a much larger 64,000 base pair region yields only 136 instances of the core TTAGGG hexamer, far short of a telomere’s structure. Crucially, the orientation is often wrong – TTAGGG motifs appear where CCCTAA should be, and vice-versa. This messy, sparse arrangement hardly resembles the robust structure expected from even an ancient, degraded fusion event.

Furthermore, creationist biologist Dr. Jeffrey Tomkins discovered that this alleged fusion site is not merely inactive debris; it falls squarely within a functional region of the DDX11L2 gene, likely acting as a promoter or regulatory element (Tomkins, 2013). Why would a supposedly non-functional scar from an ancient fusion land precisely within, and potentially regulate, an active gene? This finding severely undermines the idea of it being simple evolutionary leftovers.

The Phantom Centromere

A standard chromosome has one centromere. Fusing two standard chromosomes would initially create a dicentric chromosome with two centromeres – a generally unstable configuration. The fusion hypothesis thus predicts that one of the original centromeres must have been inactivated, leaving behind a remnant or “cryptic” centromere on Chromosome 2.

Proponents point to alpha-satellite DNA sequences found around locus 2q21 as evidence for this inactivated centromere, citing studies like Avarello et al. (1992) and the chromosome sequencing paper by Hillier et al. (2005). But this evidence is weak. Alpha-satellite DNA is indeed common near centromeres, but it’s also found abundantly elsewhere throughout the genome, performing various functions.

The Avarello study, conducted before full genome sequencing, used methods that detected alpha-satellite DNA generally, not functional centromeres specifically. Their results were inconsistent, with the signal appearing in less than half the cells examined – hardly the signature of a definite structure. Hillier et al. simply noted the presence of alpha-satellite tracts, but these specific sequences are common types found on nearly every human chromosome and show no unique similarity or phylogenetic clustering with functional centromere sequences. There’s no compelling structural or epigenetic evidence marking this region as a bona fide inactivated centromere; it’s simply a region containing common repetitive DNA.

Uniqueness and the Mutation Rate Fallacy

Adding to the puzzle, the specific short sequence often pinpointed as the precise fusion point isn’t unique. As can be demonstrated using the BLAT tool, this exact sequence appears on human Chromosomes 7, 19, and the X and Y chromosomes. If this sequence is the unique hallmark of the fusion event, why does it appear elsewhere? The evolutionary suggestion that these might be remnants of other, even more ancient fusions is pure speculation without a shred of supporting evidence.

The standard evolutionary counter-argument to the lack of clear telomere and centromere signatures is degradation over time. “The fusion happened millions of years ago,” the reasoning goes, “so mutations have scrambled the evidence.” However, this explanation crumbles under the weight of actual mutation rates.

Using accepted human mutation rate estimates (Nachman & Crowell, 2000) and the supposed 6-million-year timeframe since divergence from chimps, we can calculate that the specific ~800 base pair fusion region would be statistically unlikely to have suffered even one mutation during that entire period! The observed mutation rate is simply far too low to account for the dramatic degradation required to turn thousands of pristine telomere repeats and a functional centromere into the sequences we see today. Ironically, the known mutation rate argues against the degradation explanation needed to salvage the fusion hypothesis.

Common Design vs. Common Ancestry

What about the general similarity in gene order (synteny) between human Chromosome 2 and chimpanzee chromosomes 2A and 2B? While often presented as strong evidence for fusion, similarity does not automatically equate to ancestry. An intelligent designer reusing effective plans is an equally valid, if not better, explanation for such similarities. Moreover, the “near identical” claim is highly exaggerated; large and significant differences exist in gene content, control regions, and overall size, especially when non-coding DNA is considered (Tomkins, 2011, suggests overall similarity might be closer to 70%). This makes sense when considering that coding regions function to provide the recepies for proteins (which similar life needs will share similarly).

Conclusion: A Story Of Looking for Evidence

When the genetic data for human Chromosome 2 is examined without the pre-commitment to an evolutionary narrative, the evidence for the fusion event appears remarkably weak. So much so that it begs the question, was this a mad-dash to explain the blatent differences in the genomes of Humans and Chimps? The expected telomere signature is absent, replaced by a short, jumbled sequence residing within a functional gene region. The evidence for a second, inactivated centromere relies on the presence of common repetitive DNA lacking specific centromeric features. The supposed fusion sequence isn’t unique, and known mutation rates are woefully insufficient to explain the degradation required by the evolutionary model over millions of years.

The chromosome 2 fusion story seems less like a conclusion drawn from compelling evidence and more like an interpretation imposed upon ambiguous data to fit a pre-existing belief in human-ape common ancestry. The scientific data simply does not support the narrative. Perhaps it’s time to acknowledge that the “evidence” for this iconic fusion event may indeed be derived largely “out of thin air.”

References:

- Avarello, R., Pedicini, A., Caiulo, A. et al. (1992). Evidence for an ancestral alphoid domain on the long arm of human chromosome 2. Hum Genet 89, 247–249. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00217134

- Hillier, L., Graves, T., Fulton, R. et al. (2005). Generation and annotation of the DNA sequences of human chromosomes 2 and 4. Nature 434, 724–731. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature03466

- IJdo JW, Baldini A, Ward DC, Reeders ST, Wells RA. (1991). Origin of human chromosome 2: an ancestral telomere-telomere fusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 88(20):9051-5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.20.9051.

- Nachman, M. W., & Crowell, S. L. (2000). Estimate of the mutation rate per nucleotide in humans. Genetics, 156(1), 297–304. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/156.1.297

- Tomkins, J. P. (2011). How Genomes are Sequenced and Why it Matters: Implications for Studies in Comparative Genomics of Humans and Chimpanzees. Answers Research Journal, 4, 81-88. Retrieved from https://answersresearchjournal.org/sequence-human-chimpanzee-genomes/

- Tomkins, J.P. (2013). Alleged Human Chromosome 2 Fusion Site Encodes an Active DNA Binding Domain Inside a Complex Repeats Region. Answers Research Journal, 6, 367–375. Retrieved from https://answersresearchjournal.org/human-chromosome-2-fusion-site-encodes-active-dna-binding-domain/

Leave a comment