Introduction

Evolution by natural selection is a foundational theory in biology, observable in bacteria developing resistance, finch beak size changes, and populations adapting to environments. These microevolution examples are experimentally verified and widely accepted.

A deeper question persists: Are the mechanisms of random mutation and natural selection sufficient to explain not only the modification of existing biological structures, but also their original creation? Specifically, can the processes observed in generating variation within species account for the origin of entirely novel protein folds, enzymatic functions, and the fundamental molecular machinery of life?

This essay addresses this question by systematically evaluating the proposed mechanisms for evolutionary innovation, identifying their constraints, and highlighting what appears to be a fundamental limit: the origin of complex protein architecture.

Part I: The Mechanisms of Modification

Gene Duplication: Copy, Paste, Edit

The most commonly cited mechanism for evolutionary innovation is gene duplication. The logic is straightforward: when a gene is accidentally copied during DNA replication, the organism now has two versions. One copy maintains the original function (keeping the organism alive), while the redundant copy is “free” to mutate without immediate lethal consequences.

In theory, this freed copy can acquire new functions through random mutation—a process called neofunctionalization. Over time, what was once a single-function gene becomes a gene family with diverse, related functions.

This mechanism is real and well-documented. For instance, in “trio” studies (father, mother, child), we regularly see de novo copy number variations (CNVs). Based on this, we can trace gene families back through evolutionary history and see convincing evidence of duplication events. However, gene duplication has important limitations:

Dosage sensitivity: Cells operate as finely tuned chemical systems. Doubling the amount of a protein often disrupts this balance, creating harmful or even lethal effects. The cell isn’t simply tolerant of extra copies—duplication frequently imposes an immediate cost.

Subfunctionalization: Rather than one copy evolving a bold new function, duplicate genes more commonly undergo subfunctionalization—they degrade slightly and split the original function between them. What was once done by one gene is now accomplished by two, each doing part of the job. This adds genomic complexity but doesn’t create novel capabilities.

The prerequisite problem: Most fundamentally, gene duplication requires a functional gene to already exist. It’s a “copy-paste-edit” mechanism. It can explain variations on a theme—how you get a family of related enzymes—but it cannot explain the origin of the first member of that family.

Evo-Devo: Rewiring the Switches

Evolutionary developmental biology (evo-devo) revealed something crucial: many major morphological changes don’t come from inventing new genes, but from rewiring when and where existing genes are expressed. Mutations in regulatory elements—the “switches” that control genes—can produce dramatic changes in body plans.

A classic example: the difference between a snake and a lizard isn’t that snakes invented fundamentally new genes. Rather, mutations in regulatory regions altered the expression patterns of Hox genes (master developmental regulators), eliminating limb development while extending the body axis.

This mechanism helps explain how evolution can produce dramatic morphological diversity without constantly inventing new molecular parts. But it has clear boundaries:

The circuitry prerequisite: Regulatory evolution presupposes the existence of a sophisticated, modular regulatory network—the Hox genes themselves, enhancer elements, transcription factor binding sites. This network is enormously complex. Evo-devo explains how to rearrange the blueprint, but not where the drafting tools came from.

Modification, not creation: You can turn genes on in new places, at new times, in new combinations. You can lose structures (snakes losing legs). But you cannot regulatory-mutate your way to a structure whose genetic basis doesn’t already exist. You’re rearranging existing parts, not forging new ones.

Exaptation: Shifting Purposes

Exaptation describes how traits evolved for one function can be co-opted for another. Feathers, possibly first used for insulation or display, were later recruited for flight. Swim bladders in fish became lungs in land vertebrates.

This is an important concept for understanding evolutionary pathways—it explains how structures can be preserved and refined even when their ultimate function hasn’t yet emerged. But exaptation is a description of changing selective pressures, not a mechanism of generation. It tells us how a trait might survive intermediate stages, but not how the physical structure arose in the first place.

Part II: The Hard Problem—De Novo Origins

The mechanisms above all share a common feature: they are remixing engines. They shuffle, duplicate, rewire, and repurpose existing genetic material. This works brilliantly for generating diversity and adaptation. But it raises an unavoidable question: Where did the original material come from?

This is where the inquiry becomes more challenging.

De Novo Gene Birth: From Junk to Function?

To tackle this question, we examine the hypothesis that new genes can arise from previously non-coding “junk” DNA—an idea central to de novo gene birth.

One hypothesis is that non-coding DNA—sometimes called “junk DNA”—occasionally gets transcribed randomly. If a random mutation creates an open reading frame (a start codon, some codons, a stop codon), you might produce a random peptide. Perhaps, very rarely, this random peptide does something useful, and natural selection preserves and refines it.

This mechanism has some support. We do see “orphan genes” in various lineages—genes with no clear homologs in related species, suggesting recent origin. When we examine these orphan genes, many are indeed simple: short, intrinsically disordered proteins with low expression levels.

But here’s where we hit the toxicity filter—a fundamental physical constraint.

The Toxicity Filter

Protein synthesis is energetically expensive, consuming up to 75% of a growing cell’s energy budget. When a cell produces a protein, it’s making an investment. If that protein immediately misfolds and gets degraded by the proteasome, the cell has just run a futile cycle—burning energy to produce garbage.

In a competitive environment (which is where natural selection operates), a cell wasting energy on useless proteins will be outcompeted by leaner, more efficient cells. This creates strong selection pressure against expressing random, non-functional sequences.

It gets worse. Cells have a limited capacity for handling misfolded proteins. Chaperone proteins help fold new proteins correctly, and the proteasome system degrades those that fail. But these are finite resources. If a cell produces too many difficult-to-fold or misfolded proteins, it triggers the Unfolded Protein Response (UPR).

The UPR is an emergency protocol. Initially, the cell tries to fix the problem—producing more chaperones, slowing translation. But if the stress is too severe, the UPR switches from “repair” to “abort”: the cell undergoes apoptosis (programmed cell death) to protect the organism.

This creates a severe constraint: natural selection doesn’t just fail to reward complex random sequences—it actively punishes them. The toxicity filter eliminates complex precursors before they have a chance to be refined.

The Result

The “reservoir” of potentially viable de novo genes is therefore biased heavily toward simple, disordered, low-expression peptides. These can slip through because they don’t trigger the toxicity filters. They don’t misfold (because they don’t fold), and at low expression, they don’t drain significant resources.

This explains the orphan genes we observe: simple, disordered, regulatory, or binding proteins. But it fails to explain the origin of complex, enzymatic machinery—proteins that require specific three-dimensional structures to catalyze reactions.

Part III: The Valley of Death

To understand why complex enzymatic proteins are so difficult to generate de novo, we need to examine what makes them different from simple disordered proteins.

Two Types of Proteins

Intrinsically Disordered Proteins (IDPs) are floppy, flexible chains. They’re rich in polar and charged amino acids (hydrophilic—“water-loving”). These amino acids are happy interacting with water, so the protein doesn’t collapse into a compact structure. IDPs are excellent for binding to other molecules (they can wrap around things) and for regulatory functions (they’re flexible switches). They’re also relatively safe—they don’t aggregate easily.

Folded Proteins, by contrast, have a hydrophobic core. Water-hating amino acids cluster in the center of the protein, away from the surrounding water. This hydrophobic collapse creates a stable, specific three-dimensional structure. Folded proteins can do things IDPs cannot: precise catalysis requires holding a substrate molecule in exactly the right geometry, which requires a rigid, well-defined active site pocket.

The problem is that the “recipe” for these two types of proteins is fundamentally different. You can’t gradually transition from one to the other without passing through a dangerous intermediate state.

The Sticky Globule Problem

Imagine trying to evolve from a safe IDP to a functional folded enzyme:

- Start: A disordered protein—polar amino acids, floppy, safe.

- Intermediate: As you mutate polar residues to hydrophobic ones, you don’t immediately get a nice folded structure. Instead, you get a partially hydrophobic chain—the worst of both worlds. These “sticky globules” are aggregation-prone. They clump together like glue, forming toxic aggregates.

- End: A properly folded protein with a hydrophobic core and stable structure

The middle step—the sticky globule phase—is precisely what the toxicity filter eliminates most aggressively. These partially hydrophobic intermediates are the most dangerous type of protein for a cell.

This creates what we might call the Valley of Death: a region of sequence space that is selected against so strongly that random mutation cannot cross it. To get from a safe disordered protein to a functional enzyme, you’d need to traverse this valley—but natural selection is actively pushing you back.

Catalysis Requires Geometry

There’s a second constraint. Catalysis—the acceleration of chemical reactions—almost always requires a precise three-dimensional pocket (an active site) that can:

- Position the substrate molecule correctly.

- Stabilize the transition state.

- Shield the reaction from water (in many cases)

A floppy disordered protein is excellent for binding (it can wrap around things), but terrible for catalysis. It lacks the rigid geometry needed to precisely orient molecules and stabilize reaction intermediates.

This means the “functional gradient” isn’t smooth. You can evolve binding functions with IDPs. You can evolve regulatory functions. But to evolve enzymatic function, you need to cross the valley—and the valley actively resists crossing.

Part IV: The Escape Route—And Its Implications

There is one clear escape route from the Valley of Death: don’t cross it at all.

Divergence from Existing Folds

If you already have a stable folded protein—one with a hydrophobic core and a defined structure—you can modify it safely:

- Duplicate it: Now you have a redundant copy.

- Keep the core: The hydrophobic core (the “dangerous” part) stays conserved. This maintains structural stability.

- Mutate the surface: The active site is usually on flexible loops outside the core. Mutate these loops to change substrate specificity, reaction type, or regulation.

This mechanism is well-documented. It’s how modern enzyme families diversify. You get proteins that are functionally very different (digesting different substrates, catalyzing different reactions) but structurally similar—variations on the same fold.

Critically, you never cross the Valley of Death because you never dismantle the scaffold. You’re modifying an existing, stable structure, not building one from scratch.

The Primordial Set

This escape route, however, comes with a profound implication: it presupposes the fold already exists.

If modern enzymatic diversity arises primarily through divergence from existing folds rather than de novo generation of new folds, where did those original folds come from?

The empirical data suggest a striking answer: they arose very early, and there hasn’t been much architectural innovation since.

When we examine protein structures across all domains of life, we don’t see a continuous spectrum of novel shapes appearing over evolutionary time. Instead, we see roughly 1,000-10,000 basic structural scaffolds (fold families) that appear again and again. A bacterial enzyme and a human enzyme performing completely different functions often share the same underlying fold—the same basic architectural plan.

Comparative genomics pushes this pattern even further back. The vast majority of these fold families appear to have been present in LUCA—the Last Universal Common Ancestor—over 3.5 billion years ago.

The implication is stark: evolution seems to have experienced a “burst” of architectural invention right at the beginning, and has spent the subsequent 3+ billion years primarily as a remixer and optimizer, not an architect of fundamentally new structures.

Part V: The Honest Reckoning

We can now reassess the original question: Are the mechanisms of mutation and natural selection sufficient to explain not just the modification of life, but its origination?

What the Mechanisms Can Do

The neo-Darwinian synthesis is extraordinarily powerful for explaining:

- Optimization: Taking an existing trait and refining it

- Diversification: Creating variations on existing themes

- Adaptation: Adjusting populations to new environments

- Loss: Eliminating unnecessary structures

- Regulatory rewiring: Changing when and where genes are expressed

These mechanisms are observed, experimentally verified, and sufficient to explain the vast majority of biological diversity we see around us.

What the Mechanisms Struggle With

The same mechanisms face severe constraints when attempting to explain:

- The origin of novel protein folds: The Valley of Death makes de novo generation of complex, folded, enzymatic proteins implausible under cellular conditions.

- The origin of the primordial set: The fundamental protein architectures that all modern life relies on

- The origin of the cellular machinery: DNA replication, transcription, translation, and error correction systems that evolution requires to function

A New Theory

The constraints we’ve examined—the toxicity filter, the Valley of Death, the thermodynamics of protein folding—are not “research gaps” that might be closed with more data. They are physical constraints rooted in chemistry and bioenergetics.

Modern evolutionary mechanisms are demonstrably excellent at working with existing complexity. They can shuffle it, optimize it, repurpose it, and elaborate on it in extraordinary ways. The diversity of life testifies to its power.

But when we trace the mechanisms back to their foundation—when we ask how the original protein folds arose, how the first enzymatic machinery came to be—we encounter a genuine boundary.

The thermodynamics that make de novo fold generation implausible today presumably existed 3.5 billion years ago as well. Perhaps early Earth conditions were radically different in ways that bypassed these constraints—different chemistry, mineral catalysts, an RNA world with different rules. Perhaps there are mechanisms we haven’t yet discovered or understood.

But based on what we currently understand about the mechanisms of evolution and the physics of protein folding, the honest answer to “how did those original folds arise?” is:

They didn’t.

We need a new explanation that can account for the data. We have excellent, mechanistic explanations for how life diversifies and adapts. We have a clear understanding of the constraints that limit those mechanisms. And we have an unsolved problem at the foundation.

The question remains open: not as a gap in data, but as a gap in mechanism. So what mechanism can account for genetic diversity?

Part VI: A More Parsimonious Model

For over a century, the primary explanation for the vast diversity of life on Earth has been the slow accumulation of mutations over millions of years, filtered by natural selection. However, there is another account of the origins of life that is often left unacknowledged and dismissed as pseudoscience. The concept is simple. We see information in the form of DNA, which is, by nature, a linguistic code. Codes require minds in our repeated and uniform experience. If our experience truly tells us that evolutionary mechanisms cannot account for information systems, as we’ve discovered through this inquiry, then it stands to reason that a design solution cannot rightly be said to be “off the table.

However, there are many forms of design, so which one fits the data?

The answer lies in a powerful, testable model known as Created Heterozygosity and Natural Processes (CHNP). This model suggests that a designer created organisms not as genetically uniform clones, but with pre-existing genetic diversity “front-loaded” into their genomes.

Here is why Created Heterozygosity makes scientific sense.

A common objection to any form of young-age design model is that two people cannot produce the genetic variation seen in seven billion humans today. Critics argue that we would be clones. However, this objection assumes Adam and Eve were genetically homozygous (having two identical DNA copies).

If Adam and Eve were created with heterozygosity—meaning their two sets of chromosomes contained different versions of genes (alleles)—they could possess a massive amount of potential variation.

The Power of Recombination

We observe in biology that parents pass on traits through recombination and gene conversion. These processes shuffle the DNA “deck” every generation. Even if Adam and Eve had only two sets of chromosomes each, the number of possible combinations they could produce is mind-boggling.

If you define an allele by specific DNA positions rather than whole genes, two individuals can carry four unique sets of genomic information. Calculations show that this is sufficient to explain the vast majority of common genetic variants found in humans today without needing millions of years of mutation. In fact, most allelic diversity can be explained by only two “major” alleles.

In short, the problem isn’t that two people can’t produce diversity; it’s that critics assume the starting pair had no diversity to begin with.

Part VI: A Dilemma, a Ratchet, and Other Problems

Before we go further in-depth in our explanation of CHNP, we must realise the scope of the problems with evolution. It is not just that the mechanisms are insufficient for creating novelty, that would be one thing. But we see there are insurmountable “gaps” everywhere you turn in the modern synthesis.

The “Waiting Time” Problem

The evolutionary model relies on random mutations to generate new genetic information. However, recent numerical simulations reveal a profound waiting time problem. Beneficial mutations are incredibly rare, and waiting for specific strings of nucleotides (genetic letters) to arise and be fixed in a population takes far too long.

For example, establishing a specific string of just two new nucleotides in a hominin population would take an average of 84 million years. A string of five nucleotides would take 2 billion years. There simply isn’t enough time in the evolutionary timeline (e.g., 6 million years from a chimp-like ancestor to humans) to generate the necessary genetic information from scratch.

Haldane’s Dilemma

In 1957, the evolutionary geneticist J.B.S. Haldane calculated that natural selection is not free; it has a biological “cost”. For any specific genetic variant (mutation) to increase in a population, the individuals without that trait must effectively be removed from the gene pool—either by death or by failing to reproduce.

This creates a dilemma for the evolutionary narrative:

A population only has a limited surplus of offspring available to be “spent” on selection. If a species needs to select for too many traits at once, or eliminate too many mutations, the required death rate would exceed the reproductive rate, driving the species to extinction.

Haldane calculated that for a species with a low reproductive rate like humans, the cost of fixing just one beneficial mutation would require roughly 300 generations. This speed is far too slow to explain the complexity of the human genome, even within the evolutionary timescale of millions of years.

Rarity of Function

From the perspective of Dr. Douglas Axe, a molecular biologist and Director of the Biologic Institute, there is a mathematically fatal challenge to the Darwinian narrative. His research focuses on the “rarity of function”—specifically, how difficult it is to find a functional protein sequence among all possible combinations of amino acids.

Proteins are chains of amino acids that must fold into precise three-dimensional shapes to function. There are 20 different amino acids available for each position in the chain. If you have a modest protein that is 150 amino acids long, the number of possible arrangements is 20^150. This number is roughly 10^195. To put this in perspective, there are only about 10^80 atoms in the entire observable universe.

The “search space” of possible combinations is unimaginably vast. Evolutionary theory assumes that “functional” sequences (those that fold and perform a task) are common enough that random mutations can stumble upon them. Dr. Axe tested this assumption experimentally using a 150-amino-acid domain of the beta-lactamase enzyme. In his seminal 2004 paper published in the Journal of Molecular Biology, Axe determined the ratio of functional sequences to non-functional ones.

He calculated that the probability of a random sequence of 150 amino acids forming a stable, functional fold is approximately 1 in 10^77. This rarity is catastrophic for evolution. To find just one functional protein fold by chance would be like a blindfolded man trying to find a single marked atom in the entire Milky Way galaxy. Because functional proteins are so isolated in sequence space, natural selection cannot help “guide” the process.

Natural selection only works after a function exists. It cannot select a protein that doesn’t work yet. Axe describes functional proteins as tiny, isolated islands in a vast sea of gibberish. This is precisely the Valley of Death we discussed earlier. You cannot “gradually” evolve from one island to another because the space between them is lethal (non-functional). Even if the entire Earth were covered in bacteria dividing rapidly for 4.5 billion years, the total number of mutational trials would be roughly 10^40. This is nowhere near the 10^77 trials needed to statistically guarantee finding a single new protein fold.

Muller’s Ratchet

While Haldane highlighted the cost and Axe showed the scale, Muller showed the trajectory. Muller’s Ratchet describes the mechanism of irreversible decline. The genome is not a pool of independent genes; it is organized into “linkage blocks”—large chunks of DNA that are inherited together.

Because beneficial mutations (if they occur) are physically linked to deleterious mutations on the same chromosome segment, natural selection cannot separate them. As deleterious mutations accumulate within these linkage blocks, the overall genetic quality of the block declines. Like a ratchet that only turns one way, the damage locks in. The “best” class of genomes in the population eventually carries more mutations than the “best” class of the previous generation. Over time, every linkage block in the human genome accumulates deleterious mutations faster than selection can remove them. There is no mechanism to reverse this damage, leading to a continuous, downward slide in genetic information.

Genetic Entropy

According to Dr. Sanford, these factors together create a lethal dilemma for the standard evolutionary model. The combination of high mutation rates, vast fitness landscapes, the high cost of selection, and physical linkage ensures that the human genome is rusting out like an old car, losing information with every generation.

If humanity had been accumulating mutations for millions of years, our genome would have already reached “error catastrophe,” and we would be extinct. Alexey Kondrashov described this phenomenon in his paper, “Why Have We Not Died 100 Times Over?” The fact that we are still here suggests we have only been mutating for thousands, not millions, of years.

The vast majority of mutations are harmful or “nearly neutral” (slightly harmful but invisible to natural selection). These mutations accumulate every generation. Human mutation rates indicate we are accumulating about 100 new mutations per person per generation. If humanity were hundreds of thousands of years old, we would have gone extinct from this genetic load.

Created Heterozygosity aligns with this reality. It posits a perfect, highly diverse starting point that is slowly losing information over time, rather than a simple starting point struggling to build information against the tide of entropy. The observed degeneration is also consistent with the Biblical account of a perfect Creation that was subjected to corruption and decay following the Fall.

Rapid Speciation

Proponents of CHNP do not believe in the “fixity of species.” Instead, they observe that species change and diversify over time—often rapidly. This is called “cis-evolution” (diversification within a kind) rather than “trans-evolution” (changing from one kind to another).

Speciation often occurs when a sub-population becomes isolated and loses some of its initial genetic diversity, shifting from a heterozygous state to a more homozygous state. This reveals specific traits (phenotypes) that were previously hidden (recessive). These changes will inevitably make two populations reproductively isolated or incompatible over several generations. This particular form of speciation is sometimes called Mendelian speciation.

Real-world examples of this can easily be found. We see this in the rapid diversification of cichlid fish in African lakes, which arose from “ancient common variations” rather than new mutations. We also see it in Darwin’s finches, where hybridization and isolation lead to rapid changes in beak size and shape. In fact, this phenomenon is so prevalent that it has its own name in the literature—contemporary evolution.

Darwin himself noted that domestic breeds (like dogs or pigeons) show more diversity than wild species. If humans can produce hundreds of dog breeds in a few thousand years by isolating traits, natural processes acting on created diversity could easily produce the wild species we see (like zebras, horses, and donkeys) from a single created kind in a similar timeframe.

Molecular Clocks

Finally, when we look at Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA)—which is passed down only from mothers—we find a “clock” that fits the biblical timeline perfectly.

The number of mtDNA differences between modern humans fits a timescale of about 6,000 years, not hundreds of thousands. While mtDNA clocks suggest a recent mutation accumulation, nuclear DNA differences are too numerous to be explained by mutation alone in 6,000 years. This confirms that the nuclear diversity must be frontloaded (original variety), while the mtDNA diversity represents mutational history.

Conclusion

The Created Heterozygosity model explains the origin of species by recognizing that God engineered life with the capacity to adapt, diversify, and fill the earth. It accounts for the massive genetic variation we see today without ignoring the mathematical impossibility of evolving that information from scratch. Rather than being a reaction against science, this model embraces modern genetic data—from the limits of natural selection to the reality of genetic entropy—to provide a robust history of life.

Part VII: Created Heterozygosity & Natural Processes

The evidence for Created Heterozygosity, specifically within the Created Heterozygosity & Natural Processes (CHNP) model, makes several important predictions that distinguish it from the standard Darwinian explanations.

Prediction 1: “Major” Allelic Architecture

If the created heterozygosity is correct, each gene locus of the human line should feature no more than four predominant alleles encoding functional, distinct proteins. This is a prediction based on Adam and Eve having a total of four genome copies altogether. This prediction can be refined, however, to be even more particular.

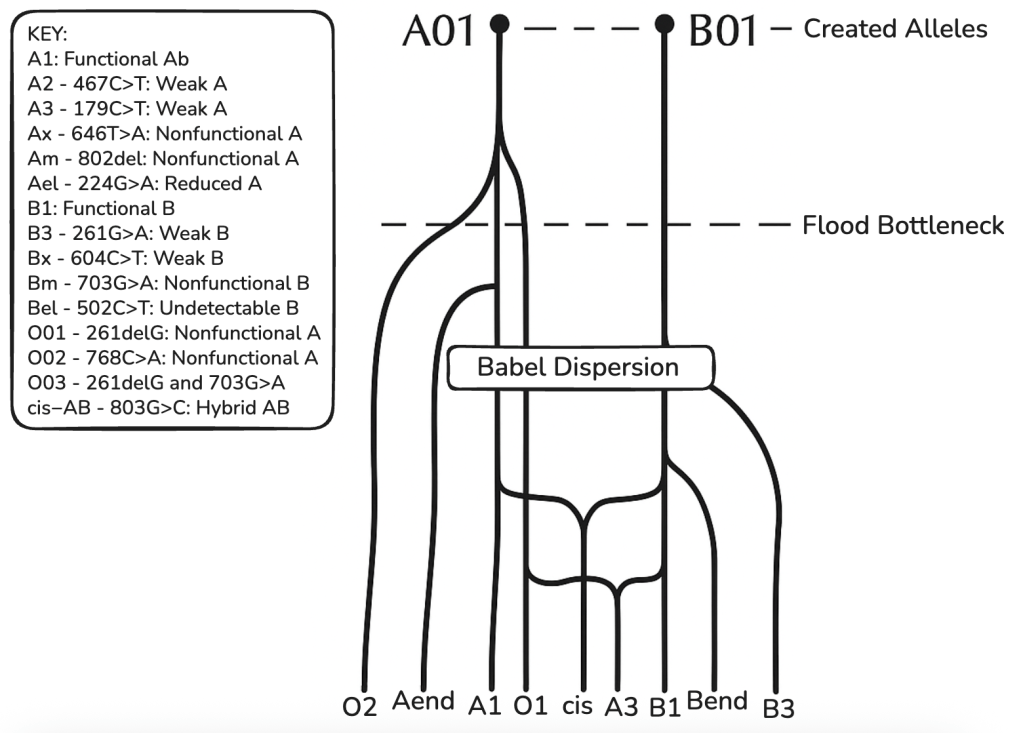

Based on an analysis of the ABO gene within the Created Heterozygosity and Natural Processes (CHNP) model, the evidence suggests there were only two major alleles in the original created pair (Adam and Eve), rather than the theoretical maximum of four, for the following reasons:

1. Only A and B are Functionally Distinct “Major” Alleles

While a single pair of humans could theoretically carry up to four distinct alleles (two per person), the molecular data for the ABO locus reveals only two distinct, functional genetic architectures: A and B. The A and B alleles code for functional glycosyltransferase enzymes. They differ from each other by only seven nucleotides, four of which result in amino acid changes that alter the enzyme’s specificity. In an analysis of 19 key human functional loci, ABO is identified as having “dual majors.” These are the foundational, optimized alleles that are highly conserved and predate human diversification. Because A and B represent the only two functional “primordial” archetypes, the CHNP model posits that the original ancestors possessed the optimal A/B heterozygous genotype.

2. The ‘O’ Allele is a Broken ‘A.’

The reason there are not three (or four) original alleles (e.g., A, B, and O) is that the O allele is not a distinct, original design. It is a degraded version of the A allele.

The most common O allele (O01) is identical to the A allele except for a single guanine deletion at position 261. This deletion causes a frameshift mutation, resulting in a truncated, non-functional enzyme. Because the O allele is simply a broken A allele, it represents a loss of information (genetic entropy) rather than originally created diversity. The CHNP model predicts that initial kinds were highly functional and optimized, containing no non-functional or suboptimal gene variants. Therefore, the non-functional O allele would not have been present in the created pair but arose later through mutation.

3. AB is Optimal For Both Parents

A critical medical argument for the AB genotype in both parents (and therefore 2 Major created alleles) concerns the immune system and pregnancy. The CHNP model suggests that an optimized creation would minimize physiological incompatibility between the first mother and her offspring.

In the ABO system, individuals naturally produce antibodies against the antigens they lack. A person with Type ‘A’ blood produces anti-B antibodies; a person with Type ‘B’ produces anti-A antibodies; and a person with Type O produces both.

Individuals with Type AB blood produce neither anti-A nor anti-B antibodies because they possess both antigens on their own cells.

If the original mother (Eve) were Type A, she would carry anti-B antibodies, which could potentially attack a Type B or AB fetus (Hemolytic Disease of the Newborn). However, if she were Type AB, her immune system would tolerate fetuses of any blood type (A, B, or AB) because she lacks the antibodies that would attack them.

If there were more than two original antigens, these problems would be inevitable. The only solution is for both parents to share the same two antigens.

4. Disclaimer about scope

This, along with many other examples within the gene catalogue, suggests most, if not all, original gene loci were bi-allelic for homozygosity. This is not to say all were, as we do not have definitive proof of that, and there are several, e.g., immuno-response genes, loci which could theoretically have more than two Majors. However, it is highly likely that all genetic diversity can be explained by bi-genome, and not quad-genome, diversity. Greater modern diversity, if present, can consistently be partitioned into two functional clades, with subsidiary alleles emerging via SNPs, InDels, or recombinations over short timescales.

Prediction 2: Cross-Species Conservation

Having similar genes is essential in a created world in order for ecosystems to exist; it shouldn’t be surprising that we share DNA with other organisms. From that premise, it follows that some organisms will be more or less similar, and those can be categorized. Due to the laws of physics and chemistry, there are inherent design constraints on forms of biota. Due to this, it is expected that there will be functional genes that are shared throughout life where they are applicable. For instance, we share homeobox genes with much of terrestrial life, even down to snakes, mice, flies, and worms. These genes are similar because they have similar functions. This is precisely what we would predict from a design hypothesis.

Both models (CHNP and EES) predict that there will be some shared functional operations throughout all life. Although this prediction does lean more in favor of a design hypothesis, it is roughly agnostic evidence. However, what is a differentiating prediction is that “major” alleles will persist across genera, reflecting shared functional design principles, whereas non-functional variants will be species-specific. This prediction is due to the two models ’ different understandings of the power of evolutionary processes to explain diversity.

This prediction can be tested (along with the first) by examining allelic diversity (particularly in sequence alignment) across related and non-related populations. For instance, take the ABO blood type gene again. The genetic data confirm that functional “major” alleles are conserved across species boundaries, while non-functional variants are species-specific and recent.

1. Major Alleles (A and B): Shared Functional Design

Both models acknowledge that the functional A and B alleles are shared between humans and other primates (and even some distinct mammals). However, the interpretation differs, and the CHNP model posits this as evidence of major allelic architecture—original, front-loaded functional templates.

The functional A and B alleles code for specific glycosyltransferase enzymes. Sequence analysis shows that humans, chimpanzees, and bonobos share the exact same genetic basis for these polymorphisms. This fits the prediction that “major” alleles represent the optimized, original design. Because these alleles are functional, they are conserved across genera (trans-species), reflecting a common design blueprint rather than convergent evolution or deep-time descent.

Standard evolution attributes this to “trans-species polymorphism,” arguing that these alleles have been maintained by “balancing selection” for 20 million years, predating the divergence of humans and apes.

2. Non-Functional Alleles (Type O): The Differentiating Test

The crucial test arises when examining the non-functional ‘O’ allele. Because the ‘O’ allele confers a survival advantage against severe malaria, the standard evolutionary model must do one of the following: 1) explain why it is not the case that A and B, the ‘O’ alleles are not all three ancient and shared across lineages (trans-species inheritance), or provide an example of a shared ‘O’ allele across a kind-boundary. The reason why this prediction must follow is that the ‘O’ allele, being the null version, by evolutionary definition must have existed prior to either ‘A’ or ‘B’. What’s more, ‘A’ and ‘B’ alleles can easily break and the ‘O’ is not significant enough to be selected out of a given population.

In humans, the most common ‘O’ allele (O01) results from a specific single nucleotide deletion (a guanine deletion at position 261), causing a frameshift that breaks the enzyme. However, sequence analysis of chimpanzees and other primates reveals that their ‘O’ alleles result from different, independent mutations.

Human and non-human primate ‘O’ alleles are species-specific and result from independent silencing mutations. The mutation that makes a chimp Type ‘O’ is not the same mutation that makes a human Type ‘O’.

This supports the CHNP prediction that non-functional variants arise after the functional variants from recent genetic entropy (decay) rather than ancient ancestry. The ‘O’ allele is not a third “created” allele; it is a broken ‘A’ allele that occurred independently in humans and chimps after they were distinct populations. It has become fixated in populations, such as those native to the Americas, due to the beneficial nature of the gene break.

This brings us, also, back to the evolutionary problems we mentioned. Even if these four or more beneficial mutations could occur to create one ‘A’ or ‘B’ allele, which we discussed as being incredibly unlikely, either gene would break likely at a faster rate (due to Muller’s Ratchet) than could account for the fixity of A and B in primates and other mammals.

3. Timeline and Entropy

The mutational pathways for the human ‘O’ allele fit a timeline of <10,000 years, appearing after the initial “major” alleles were established. This aligns with the CHNP view that variants arise via minimal genetic changes (SNPs, Indels) within the last 6,000–10,000 years.

The emergence of the ‘O’ allele is an example of cis-evolution (diversification within a kind via information loss). It involves breaking a functional gene to gain a temporary survival advantage (malaria resistance), which is distinct from the creation of new biological information.

4. Broader Loci Analysis

This pattern is not unique to ABO. An analysis of 19 key human functional loci (including genes for immunity, metabolism, and pigmentation) confirms the “Major Allele” prediction:

Out of the 19 loci, 16 exhibit a single (or dual, like ABO) major functional allele that is highly conserved across species. Meaning that the functional versions of the genes are shared with other primates, mammals, vertebrates, or even eukaryotes. In contrast, non-functional or pathogenic variants (such as the CCR5-Δ32 deletion or CFTR mutations) are predominantly human-specific and arose recently (often <10,000 years ago). And when similar non-functional traits appear in different species (e.g., MC1R-loss, or ‘O’ blood group), they are due to convergent, independent mutations, not shared ancestry.

To illustrate this point, below is a graph from the paper testing the CHNP model in 19 functional genes. Table 1 summarizes key metrics for each locus. Across the dataset, 84% (16/19) exhibit a single major functional allele conserved >90% across mammals/primates, with variants emerging <50,000 years ago (kya). ABO and HLA-DRB1 align with dual ancient clades; SLC6A4 shows neutral biallelic drift. Non-functional variants (e.g., nulls, deficiencies) are human-specific in 89% of cases, often via single SNPs/InDels.

| Locus | Major Allele(s) | Functional Groups (Ancient?) | Cross-Species Conservation | Variant Derivation (Changes/Time) | Model Fit (1/2/3) |

| HLA-DRB1 | Multiple lineages (e.g., *03, *04) | 2+ ancient clades (pre-Homo-Pan) | High in primates (trans-species) | Recombinations/SNPs; post-speciation (~100 kya) | Strong (clades); Partial (multi); Strong |

| ABO | A/B (O derived) | 2 ancient (A/B trans-species) | High in primates | Inactivation (1 nt del.); <20 kya | Strong; Strong; Strong |

| LCT | Ancestral non-persistent (C/C) | 1 major | High across mammals | SNPs (e.g., -13910T); ~10 kya | Strong; Strong; Strong |

| CFTR | Wild-type (non-ΔF508) | 1 major | High across vertebrates | 3 nt del. (ΔF508); ~50 kya | Strong; Strong; Strong |

| G6PD | Wild-type (A+) | 1 major | High (>95% identity) | SNPs at conserved sites; <10 kya | Strong; Strong; Strong |

| APOE | ε4 (ancestral) | 1 major (ε3/2 derived) | High across mammals | SNPs (Arg158Cys); <200 kya | Strong; Strong; Partial |

| CYP2D6 | *1 (wild-type) | 1 major | Moderate in primates | Deletions/duplications; recent | Strong; Partial; Strong |

| FUT2 | Functional secretor | 1 major | High in vertebrates | Truncating SNPs; ancient nulls (~100 kya) | Strong; Strong; Partial |

| HBB | Wild-type (HbA) | 1 major | High across vertebrates | SNPs (e.g., sickle Glu6Val); <10 kya | Strong; Strong; Strong |

| CCR5 | Wild-type | 1 major | High in primates | 32-bp del.; ~700 ya | Strong; Strong; Strong |

| SLC24A5 | Ancestral Ala111 (dark skin) | 1 major | High across vertebrates | Thr111 SNP; ~20–30 kya | Strong; Strong; Strong |

| MC1R | Wild-type (eumelanin) | 1 major | High across mammals | Loss-of-function SNPs; convergent in some | Strong; Partial (conv.); Strong |

| ALDH2 | Glu504 (active) | 1 major | High across eukaryotes | Lys504 SNP; ~2–5 kya | Strong; Strong; Strong |

| HERC2/OCA2 | Ancestral (brown eyes) | 1 major | High across mammals | rs12913832 SNP; ~10 kya | Strong; Strong; Strong |

| SERPINA1 | M allele (wild-type) | 1 major | High in mammals (family expansion) | SNPs (e.g., PiZ Glu342Lys); recent | Strong; Strong; Strong |

| BRCA1 | Wild-type | 1 major | High in primates | Frameshifts/nonsense; <50 kya | Strong; Strong; Strong |

| SLC6A4 | Long/short 5-HTTLPR | 2 neutrally evolved | High across animals | InDel (VNTR); ancient (~500 kya) | Partial; Strong; Partial |

| PCSK9 | Wild-type | 1 major | High in primates (lost in some mammals) | SNPs (e.g., Arg469Trp); recent | Strong; Strong (conv. loss); Strong |

| EDAR | Val370 (ancestral) | 1 major | High across vertebrates | Ala370 SNP; ~30 kya | Strong; Strong; Strong |

Table 1: Evolutionary Profiles of Analyzed Loci. Model Fit: Tenet 1 (major architecture), 2 (conservation), 3 (derivation). “Partial” indicates minor deviations (e.g., multi-clades or potentially >10 kya).

This is devastating for modern synthesis. If the pattern that arises is one of shared functions and not shared mistakes, the theory is dead on arrival.

Prediction 3: Derivation Dynamics

Another important prediction to consider is due to the timeline for creating heterozygosity. If life were designed young (an entailment for CHNP), variant alleles must have arisen from “majors” through minimal modifications, feasible within roughly 6 to 10 thousand years.

To look at the ABO blood group once more, we see the total feasibility of this prediction. The ABO blood group, again, offers a “cornerstone” example, demonstrating how complex diversity collapses into simple, recent mutational events.

1. The ABO Case Study: Minimal Modification

The CHNP model identifies the A and B alleles as the original, front-loaded “major” alleles created in the founding pair. The diversity we see today (such as the various O alleles and A subtypes) supports the prediction of minimal, recent modification:

As we’ve discussed, the most common O allele (O01) is not a novel invention; it is a broken ‘A’ allele. It differs from the ‘A’ allele by a single guanine deletion at position 261. This minute change causes a frameshift that renders the enzyme non-functional. Other ABO variants show similar minimal changes. The A2 allele (a weak version of A) results from a single nucleotide deletion and a point mutation. The B3 allele results from point mutations that reduce enzymatic activity.

These are not complex architectural changes requiring millions of years. They are “typos” in the code. Molecular analysis confirms that the mutation causing the O phenotype is a common, high-probability event.

2. The Mathematical Feasibility of the Timeline

A mathematical breakdown can be used to demonstrate that these variants would inevitably arise within a young-earth timeframe using standard mutation rates.

Using a standard mutation rate (1.5×10^−8 per base pair per generation) and an exponentially growing population (starting from founders), mutations accumulate rapidly and easily. Calculations suggest that in a population growing from a small founder group, the first expected mutations in the ABO exons would appear as early as Generation 4 (approx. 80 years). Over a period of 5,000 years, with a realistic population growth model, the 1,065 base pairs of the ABO exons would theoretically experience tens of thousands of mutation events. The gene would be thoroughly saturated, meaning virtually every possible single-nucleotide change would have occurred multiple times.

Specific estimates for the emergence of the ‘O’ allele place it within 50 to 500 generations (1,000 to 10,000 years) under neutral drift, or even faster with selective pressure. This perfectly fits the CHNP timeline of 6,000-10,000 years.

3. Further Validation: The 19 Loci Analysis

This pattern of “Ancient Majors, Recent Variants” is not unique to ABO. The 19 key human functional loci study also confirms that this is a systemic feature of the human genome.

Across genes involved in immunity, metabolism, and pigmentation, derived variants consistently appear to have arisen within the last 10,000 years (Holocene). ALDH2: The variant causing the “Asian flush” (Glu504Lys) is estimated to be ~2,000 to 5,000 years old. LCT (Lactase Persistence): The mutation allowing adults to digest milk arose ~10,000 years ago, coinciding with the advent of dairy farming. HBB (Sickle Cell): The hemoglobin variant conferring malaria resistance emerged <10,000 years ago. In 89% of the analyzed cases, these variants are caused by single SNPs or Indels derived from the conserved major allele.

The prediction that variant alleles must be derived via minimal modifications feasible within a young timeframe is strongly supported by the genetic data. The ABO system demonstrates that the “O” allele is merely a single deletion that could arise in less than 100 generations.

This confirms the CHNP view that while the “major” alleles (A and B) represent the original, complex design (Major Allelic Architecture), the variants (O, A2, etc.) are the result of recent, rapid genetic entropy (cis-evolution) that requires no deep-time evolutionary mechanisms to explain.

An ABO Blood Group Paradox

As we have run through these first three predictions of the Created Heterozygosity model, we have dealt particularly with the ABO gene and have run into a peculiar evolutionary puzzle. Let’s first speak of this paradox more abstractly in the form of an analogy:

Imagine a family of collectors who passed down two distinct types of antique coins (Coins A and B) to their descendants over centuries because those coins were valuable. If a third type of coin (Coin O) was also extremely valuable (offering protection/advantage) and easier to mint, you would predict the Ancestors would have kept Coin O and passed it down to both lineages alongside A and B. You wouldn’t expect the descendants to inherit A and B from the ancestor, but have to invent Coin O continuously from scratch every generation.

By virtue of this same logic, evolutionary models must predict that the ‘O’ allele should be ancient (20 million years) due to balancing selection. However, the genetic data shows ‘O’ alleles are recent and arose independently in different lineages. This supports the CHNP view: the original ancestors were created with functional A and B alleles (heterozygous), and the O allele is a recent mutational loss of function.

Prediction 4: Rapid Speciation and Adaptive Radiation

If created heterozygosity is true, and organisms were designed with built-in potential for adaptation given their environment, then we should expect to find mechanisms of extreme foresight that permit rapid change to external stressors. There are, in fact, many such mechanisms which are written about in the scientific literature: contemporary evolution, natural genetic engineering, epigenetics, higher agency, continuous environmental tracking, non-random evolution, evo-devo, etc.

The phenomenon of adaptive radiation—where a single lineage rapidly diversifies into many species—is clearly differentiating evidence for front-loaded heterozygosity rather than mutational evolution. Why? Because random mutation has no foresight. Random mutations do not prepare an organism for any eventuality. If it is not useful now, get rid of it. That is the mantra of evolutionary theory. That is the premise of natural selection. However, this premise is drastically mistaken.

1. Natural Genetic Engineering & Non-Random Evolution

The foundation of this alternative view is that genetic change is not accidental. Molecular biologist James Shapiro argues that cells are not passive victims of random “copying errors.” Instead, they possess “active biological functions” to restructure their own genomes. Cells can cut, splice, and rearrange DNA, often using mobile genetic elements (transposons) and retroviruses to rewrite their genetic code in response to stress. Shapiro calls the genome a “read-write” database rather than a read-only ROM.

Building on this, Dr. Lee Spetner proposed that organisms have a built-in capacity to adapt to environmental triggers. These changes are not rare or accidental but can occur in a large fraction of the population simultaneously. This work is supported by modern research from people like Dr. Michael Levin and Dr. Dennis Noble. Mutations are revealing themselves to be more and more a predictable response to environmental inputs.

2. The Architecture: Continuous Environmental Tracking (CET)

If organisms engineer their own genetics, how do they know when to do it? This is where CET provides the engineering framework.

Proposed by Dr. Randy Guliuzza, CET treats organisms as engineered entities. Just like a self-driving car, organisms possess input sensors (to detect the environment), internal logic/programming (to process data), and output actuators (to execute biological changes). In Darwinism, the environment is the “selector” (a sieve). In CET, the organism is the active agent. The environment is merely the data the organism tracks. For example, blind cavefish lose their eyes not because of random mutations and slow selection, but because they sense the dark environment and downregulate eye development to conserve energy, a process that is rapid and reversible. More precisely, the regulatory system of these cave fish specimens can detect the low salinity of cave water, which triggers the effect of blindness over a short timeframe.

3. The Software: Epigenetics

Epigenetics acts as the “formatting” or the switches for the DNA computer program. Epigenetic mechanisms (like methylation) regulate gene expression without changing the underlying DNA sequence. This allows organisms to adapt quickly to environmental cues—such as plants changing flowering times or root structures. These changes can be heritable. For instance, the environment of a parent (e.g., diet, stress) can affect the development of the offspring via RNA absorbed by sperm or eggs, bypassing standard natural selection. This blurs the line between the organism and its environment, facilitating rapid adaptation.

4. The Result: Contemporary Evolution

When these internal mechanisms (NGE, CET, Epigenetics) function, the result is Contemporary Evolution—observable changes happening in years or decades, not millions of years. Conservationists and biologists are observing “rapid adaptation” in real-time. Examples include invasive species changing growth rates in under 10 years, or the rapid diversification of cichlid fish in Lake Victoria.

For Young Earth Creationists (YEC), Contemporary Evolution validates the concept of Rapid Post-Flood Speciation. It shows that getting from the “kinds” on Noah’s Ark to modern species diversity in a few thousand years is biologically feasible.

Conclusion

So, where does the information for all this diversity come from? This is the specific model (CHNP) that explains the source of the variation being tracked and engineered.

This model posits that original kinds were created as pan-heterozygous (carrying different alleles at almost every gene locus). As populations grew and migrated (Contemporary Evolution), they split into isolated groups. Through sexual reproduction (recombination), the original heterozygous traits were shuffled. Over time, specific traits became “fixed” (homozygous), leading to new species.

This model argues that random mutation cannot bridge the gap between distinct biological forms (the Valley of Death) due to toxicity and complexity. Therefore, diversity must be the result of sorting pre-existing (front-loaded) functional alleles rather than creating new ones from scratch.

Look at it this way:

1. Mendelian Speciation/Created Heterozygosity is the Resource: It provides the massive library of latent genetic potential (front-loaded alleles).

2. Continuous Environmental Tracking is the Control System: It uses sensors and logic to determine which parts of that library are needed for the current environment.

3. Epigenetics and Natural Genetic Engineering are the Mechanisms: They are the tools the cells use to turn genes on/off (epigenetics) or restructure the genome (NGE) to express those latent traits.

4. Contemporary Evolution is the Observation: It is the visible, rapid diversification (cis-evolution) we see in nature today as a result of these internal systems working on the front-loaded information.

Together, these concepts argue that organisms are not passive lumps of clay shaped by external forces (Natural Selection), but sophisticated, engineered systems designed to adapt and diversify rapidly within their kinds.

The mechanism driving this diversity is the recombination of pre-existing heterozygous genes. Just 20 heterozygous genes can theoretically produce over one million unique homozygous phenotypes. As populations isolate and speciate, they lose their initial heterozygosity and become “fixed” in specific traits. This process, known as cis-evolution, explains diversity within a kind (e.g., wolves to dog breeds) but differs fundamentally from trans-evolution (evolution between kinds), which finds no mechanism in genetics.

The CHNP model argues that mutations are insufficient to create the original genetic information due to thermodynamic and biological constraints. De novo protein creation is hindered by a “Valley of Death”—a region of sequence space where intermediate, misfolded proteins are toxic to the cell. Natural selection eliminates these intermediates, preventing the gradual evolution of novel protein folds.

Mechanisms often cited as creative, such as gene duplication or recombination, are actually “remixing engines.” Duplication provides redundancy, not novelty, and recombination shuffles existing alleles without creating new genetic material. Because mutations are modifications (typos) rather than creations, the original functional complexity must have been present at the beginning.

Genetics reveals that organisms contain “latent” or hidden information that can be expressed later.

Information can be masked by dominant alleles or epistatic interactions (where one gene suppresses another). This allows phenotypic traits to remain hidden for generations and reappear suddenly when genetic combinations shift, facilitating rapid adaptation without new mutations.

Genetic elements like transposons can reversibly activate or deactivate genes (e.g., in grape color or peppered moths), acting as switches for pre-existing varieties rather than creators of new genes.

Summary

The genetic evidence for created heterozygosity rests on the observation that biological novelty is ancient and conserved, while variation is recent and degenerative. By starting with ancestors endowed with high levels of heterozygosity, the “forest” of life’s diversity can be explained by the rapid sorting and recombination of distinct, front-loaded genetic programs.

Leave a comment