In the realm of scientific inquiry, the intersection of epistemology (the study of knowledge) and physics often leads to profound philosophical debates. One such debate, highlighted by the clash between Kant’s universal claims and Heisenberg’s quantum observations, raises critical questions about the nature of causality and the limits of scientific knowledge.

Kant posited universal axioms about metaphysics and epistemology, suggesting that certain principles, like causality, are a priori—foundational to all experience. Heisenberg, however, proposed that these principles might not apply in the quantum realm, where observations seem to reveal phenomena without clear causal explanations. This divergence raises a fundamental question: Can scientific theories, particularly those in quantum physics, challenge or redefine the very foundations of how we understand knowledge?

The Challenge to Universal Causality

Heisenberg, in his work “Physics and Beyond,” recounts a conversation with Grete Hermann, a Kantian philosopher, who argued that causality is not an empirical assertion but a necessary presupposition for all experience. Hermann emphasized that without a strict relationship between cause and effect, our observations would be mere subjective sensations, lacking objective correlates. She questioned how quantum mechanics could “relax” the causal law and still claim to be a branch of science.

Heisenberg countered that in quantum mechanics, we only have access to statistical averages, not underlying processes. He cited the example of Radium B atoms emitting electrons, where the timing and direction of emission appear stochastic. He argued that extensive research reveals behaviors with no discernible causes, suggesting that causality breaks down at the quantum level.

Creationist Perspectives on Causality and Randomness

From a creationist perspective, the concept of randomness must be carefully examined. As David Bohm suggests in “Causality and Chance in Modern Physics,” random processes can exist within objects that are nonetheless real and independent of observation. This aligns with the idea that even seemingly random events may be governed by underlying, complex causal laws, perhaps beyond our current comprehension.

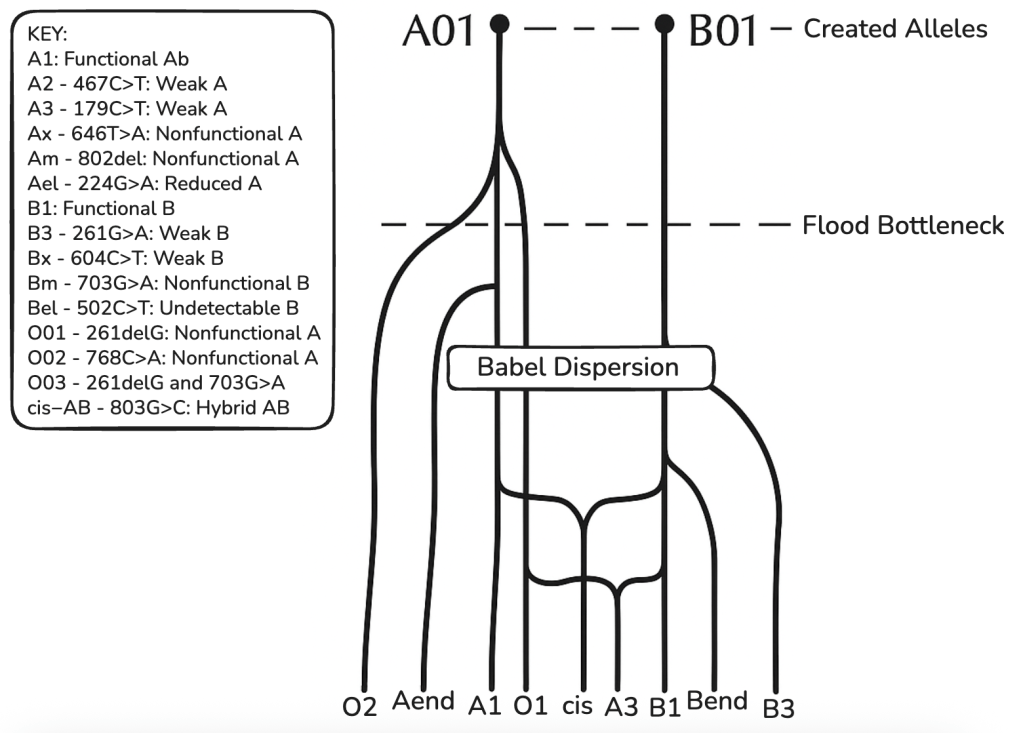

Consider the Created Heterozygosity Hypothesis, which posits that organisms were created with “front-loaded” genomes, containing a high degree of genetic variation. This variation can manifest as apparent randomness in biological processes, but it does not negate the existence of underlying design and purpose.

Furthermore, the concept of information theory, a key aspect of intelligent design, emphasizes that information is always the product of intelligent agency. The complexity and specificity observed in quantum phenomena may point to an underlying intelligence that operates beyond the limitations of our current scientific models.

Addressing the Limits of Scientific Knowledge

Hermann rightly pointed out that the absence of a discovered cause does not imply the absence of a cause. She argued that physicists should continue searching for underlying causes rather than abandoning the principle of causality altogether. This aligns with the creationist view that our understanding of the natural world is incomplete, and that further investigation may reveal deeper levels of design and purpose.

The debate between Heisenberg and Hermann highlights the limitations of science. As creationists, we acknowledge that science is a powerful tool for understanding the natural world, but it is not the ultimate arbiter of truth. Methodological naturalism, the assumption that all phenomena can be explained by natural causes, arbitrarily excludes the possibility of non-natural agency.

The Necessity of Universal Presuppositions

Kant’s emphasis on universal presuppositions, like causality, underscores the importance of a solid epistemological foundation. Without these foundational beliefs, our ability to claim objective knowledge about the world is undermined. As Friedrich clarified, “Every perception refers to an observational situation that must be specified if experience is to result. The consequence of a perception can no longer be objectified in the manner of classical physics.” However, this does not mean that Kant’s principles are wrong, but that our understanding of observation has changed.

The creationist worldview recognizes that the universe is the product of an intelligent Creator, whose design and purpose are evident in the natural world. Therefore, the search for causal explanations should not exclude the possibility of non-natural or intelligent causes.

Conclusion: A Call for Intellectual Honesty

The philosophical tension between Kant and Heisenberg reveals a fundamental issue at the intersection of epistemology and quantum physics. Heisenberg’s challenge to universal causality, while based on observed phenomena, ultimately undermines the foundation of scientific knowledge.

As creationists, we advocate for intellectual honesty and a comprehensive approach to scientific inquiry. We acknowledge the limits of science and the importance of universal presuppositions, such as causality. We recognize that our understanding of the universe is incomplete and that further investigation, guided by both scientific rigor and a biblical worldview, may reveal deeper levels of design and purpose.

The debate over causality in quantum mechanics should remind us that scientific advances, while valuable, should not lead us to abandon the foundational principles that make knowledge possible. Instead, we should embrace a holistic approach that integrates scientific observations with a robust epistemological framework, recognizing the limits of human understanding and the possibility of non-natural causes.

Sources:

Bohm, D. (1957). Causality and Chance in Modern Physics. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Heisenberg, W. (1971). Physics and Beyond: Encounters and Conversations. Harper & Row.