In the landscape of Christian apologetics, presuppositional apologetics presents a distinctive approach to understanding knowledge, reality, and belief. This philosophical method, pioneered by thinkers like Cornelius Van Til in the 1920s, challenges fundamental assumptions about epistemology and seeks to demonstrate the unique explanatory power of a biblical worldview.

Understanding Presuppositionalism

Presuppositional apologetics advances a bold claim: Christian theism provides the only coherent framework for understanding logic, morality, and the nature of knowledge itself. Unlike classical apologetic approaches that seek to prove God’s existence through external evidence, this method argues that the very possibility of rational thought depends on acknowledging a divine foundation.

The core principle is that every individual, consciously or unconsciously, operates from a set of foundational beliefs about reality. These presuppositions shape how we interpret evidence, understand causality, and construct meaning. Presuppositionalists argue that a naturalistic worldview ultimately fails to provide a stable ground for rational inquiry.

The Philosophical Challenge of Solipsism

At the heart of this approach lies a profound philosophical challenge: the problem of solipsism. If we cannot definitively prove the existence of anything beyond our own mind, how can we claim to know anything with certainty? This epistemological dilemma threatens to reduce all knowledge to a subjective, potentially illusory experience.

Traditional empiricist approaches, as critiqued by philosophers like David Hume, struggle to overcome this fundamental uncertainty. Empiricism, which relies solely on sensory experience and observation, cannot conclusively escape the possibility that our perceptions are merely internal constructs with no correspondence to an external reality.

The Divine Foundation of Knowledge

The presuppositional argument proposes a radical solution: God’s existence as the transcendent Creator provides the necessary foundation for objective knowledge. This perspective argues that:

- An objective reality exists independent of human perception

- Universal principles of logic and morality are grounded in God’s unchanging nature

- Human reasoning gains its validity from a divine source of rationality

By positioning God as the ultimate source of knowledge, this approach attempts to resolve the solipsistic dilemma. The created world, according to this view, is not a mental construct but a real, intentionally designed system that reflects divine intelligence.

Scientific and Philosophical Implications

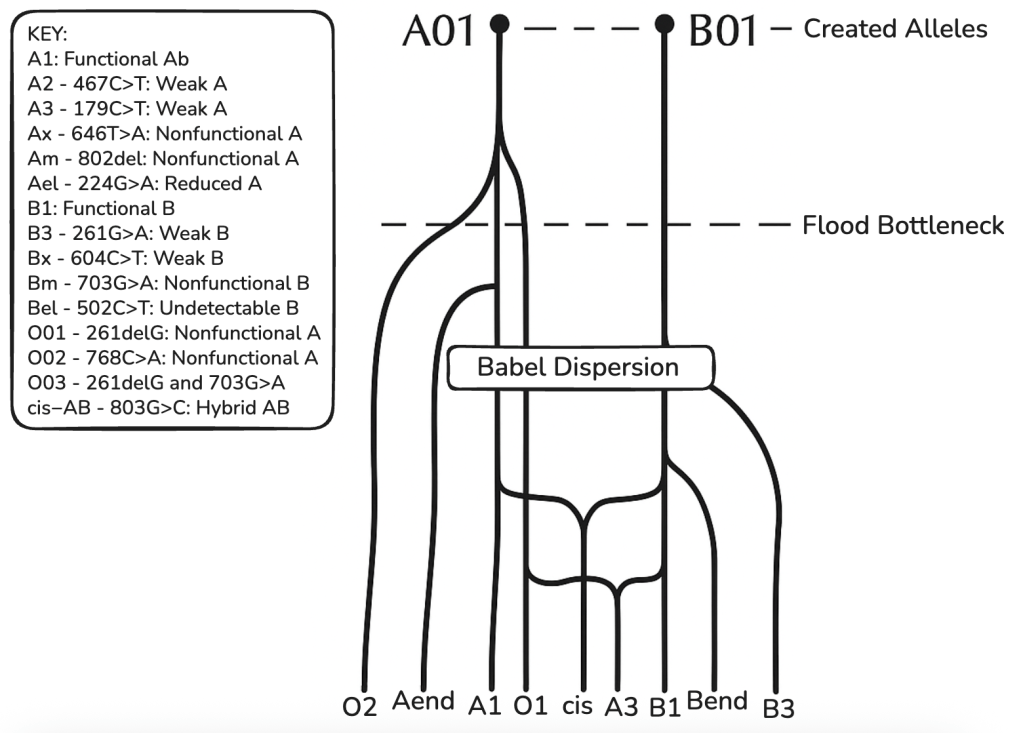

While traditional creation science is often criticized, presuppositional apologetics seeks to integrate philosophical reasoning with scientific inquiry. Concepts like baraminology (the study of created kinds) and catastrophic plate tectonics are presented as attempts to provide alternative explanatory frameworks for natural phenomena.

However, it is crucial to recognize that these arguments remain contentious within the broader scientific community. The strength of the presuppositional approach lies not in its empirical evidence but in its philosophical critique of naturalistic epistemology.

Critiques and Limitations

The presuppositional method is not without significant challenges:

- It can appear circular, assuming the very thing it seeks to prove

- It may not convincingly engage with those who do not share its initial theological premises

- It risks oversimplifying complex philosophical and scientific questions

Despite these limitations, the approach offers a provocative challenge to purely materialistic worldviews, forcing a deeper examination of the foundations of knowledge.

Conclusion

Presuppositional apologetics represents a sophisticated attempt to ground human understanding in a transcendent perspective. By challenging the foundations of knowledge and highlighting the limitations of naturalistic epistemology, it invites a more nuanced conversation about the nature of reality, reason, and belief.

While not universally convincing, this approach provides a thought-provoking framework for those seeking to understand the relationship between faith, philosophy, and scientific inquiry.