The evidence typically presented as definitive proof for the theory of common descent, the nested hierarchy of life and genetic/trait similarities, is fundamentally agnostic. This is because evolutionary theory, in its broad explanatory power, can be adapted to account for virtually any observed biological pattern post-hoc, thereby undermining the claim that these patterns represent unique or strong predictions of common descent over alternative models, such as common design.

I. The Problematic Nature of “Prediction” in Evolutionary Biology

- Strict Definition of Scientific Prediction: A true scientific prediction involves foretelling a specific, unobserved phenomenon before its discovery. It is not merely explaining an existing observation or broadly expecting a general outcome.

- Absence of Specific Molecular Predictions:

- Prior to the molecular biology revolution (pre-1950s/1960s), no scientist explicitly predicted the specific molecular similarity of DNA sequences across diverse organisms, the precise double-helix structure, or the near-universal genetic code. These were empirical discoveries, not pre-existing predictions.

- Evolutionary explanations for these molecular phenomena (e.g., the “frozen accident” hypothesis for the universal genetic code) were formulated after the observations were made, rendering them post-hoc explanations rather than predictive triumphs.

- Interpreting broad conceptual statements from earlier evolutionary thinkers (like Darwin’s “one primordial form”) as specific molecular predictions is an act of “eisegesis”—reading meaning into the text—rather than drawing direct, testable predictions from it. A primordial form does not necessitate universal code, universal protein sequences, universal logic, or universal similarity.

II. The Agnosticism of the Nested Hierarchy

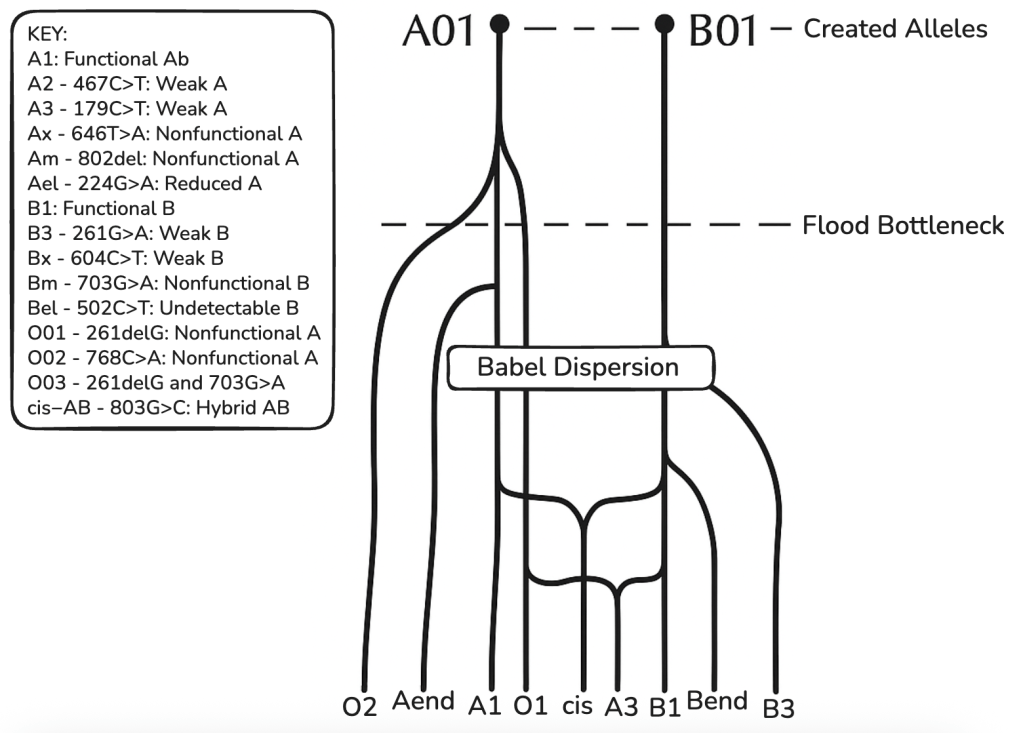

- The Nested Hierarchy as an Abstract Pattern: The observation that life can be organized into a nested hierarchy (groups within groups, e.g., species within genera, genera within families) is an abstract pattern of classification. This pattern existed and was recognized (e.g., by Linnaeus) long before Darwin’s theory of common descent.

- Compatibility with Common Design: A designer could, for various good reasons (e.g., efficiency, aesthetic coherence, reusability of components, comprehensibility), choose to create life forms that naturally fall into a nested hierarchical arrangement. Therefore, the mere existence of this abstract pattern does not uniquely or preferentially support common descent over a common design model.

- Irrelevance of Molecular “Details” for this Specific Point: While specific molecular “details” (such as shared pseudogenes, endogenous retroviruses, or chromosomal fusions) are often cited as evidence for common descent, these are arguments about the mechanisms or specific content of the nested hierarchy. These are not agnostic and can be debated fruitfully. However, they do not negate the fundamental point that the abstract pattern of nestedness itself remains agnostic, as it could be produced by either common descent or common design.

III. Evolutionary Theory’s Excessive Explanatory Flexibility (Post-Hoc Rationalization)

- Fallacy of Affirming the Consequent: The logical structure “If evolutionary theory (Y) is true, then observation (X) is expected” does not logically imply “If observation (X) is true, then evolutionary theory (Y) must be true,” especially if the theory is so flexible that it can explain almost any X.

- Capacity to Account for Contradictory or Diverse Outcomes:

- Genetic Similarity: Evolutionary theory could equally well account for a model with no significant genetic similarity between organisms (e.g., if different biochemical pathways or environmental solutions were randomly achieved, or if genetic signals blurred too quickly over time). For example, a world with extreme porportions of horizontal gene transfer (as seen in prokaryotic and rare eukaryotic cells)

- Phylogenetic Branching: The theory is flexible enough to account for virtually any observed phylogenetic branching pattern. If, for instance, humans were found to be more genetically aligned with pigs than with chimpanzees, evolutionary theory would simply construct a different tree and provide a new narrative of common ancestry. This flexability puts a wedge in any measure of predictability claimed by the theory.

- “Noise” in Data: If genetic data were truly “noise” (random and unpatterned), evolutionary theory could still rationalize this by asserting that “no creator would design that way, and randomness fully accounts for it,” thus always providing an explanation regardless of the pattern. In fact, a noise pattern is perhaps one of the few patterns better explained by random physical processes. Why would a designer, who has intentionality, create in such a slapdash way?

- Convergence vs. Divergence: The theory’s ability to explain both convergent evolution (morphological similarity without close genetic relatedness) and divergent evolution (genetic differences leading to distinct forms) should imediately signal red-flags, as this is a telltale sign of a post-hoc fitting of observations rather than a result of specific prediction.

- To illustrate this point, Let’s imagine we have seven distinct traits (A, B, C, D, E, F, G) and five hypothetical populations of creatures (P1-P5), each possessing a unique combination of these traits. For example, P1 has {A, B, C}, P2 has {A, D, E}, P3 has {A, F, G}, P4 has {B, D, F}, and P5 has {E, G}. When examining this distribution, we can construct a plausible “evolutionary story.” Trait ‘A’, present in P1, P2, and P3, could be identified as a broadly ancestral trait. P1 might be an early branch retaining traits B and C, while P2 and P3 diversified by gaining D/E and F/G respectively.

- However, the pattern becomes more complex with populations like P4 and P5. P4’s mix of traits {B, D, F} suggests it shares B with P1, D with P2, and F with P3. An evolutionary narrative would then employ concepts like trait loss (e.g., B being lost in P2/P3/P5’s lineage), convergent evolution (e.g., F evolving independently in P4 and P3), or complex branching patterns. Similarly, P5’s {E, G} would be explained by inheriting E from P2 and G from P3, while also undergoing significant trait loss (A, B, C, D, F).

- And this is the crux of the argument, given any observed distribution of traits, evolutionary theory’s flexible set of explanatory mechanisms—including common ancestry, trait gain, trait loss, and convergence—can always construct a coherent historical narrative. This ability to fit diverse patterns post-hoc renders the mere existence of a nested hierarchy, disconnected from specific underlying molecular details, as agnostic evidence for common descent over other models like common design.

IV. Challenges to Specific Evolutionary Explanations and Assumptions

- Conservation of the Genetic Code:

- The claim that the genetic code must remain highly conserved post-LUCA due to “catastrophic fitness consequences” of change is an unsubstantiated assumption. Granted, it could be true, but one can imagine plausible scenarios which could demonstrate exceptions.

- Further, evolutionary theory already postulates radical changes, including the very emergence of complex systems “from scratch” during abiogenesis. If such fundamental transformations are possible, then the notion that a “new style of codon” is impossible over billions of years, even via incremental “patches and updates,” appears inconsistent.

- Laboratory experiments that successfully engineer organisms to incorporate unnatural amino acids demonstrate the inherent malleability of the genetic code. Yet no experiment has demonstrate abiogenesis, a much more implausible event with less evolutionary time to play with. Why limit the permissible improbable things arbitrarily?

- There is no inherent evolutionary reason to expect a single, highly conserved “language” for the genetic code; if information can be created through evolutionary processes, then multiple distinct solutions should be the rule.

- Functionality of “Junk” DNA and Shared Imperfections:

- The assertion that elements like pseudogenes and endogenous retroviruses (ERVs) are “non-functional” or “mistakes” is often an “argument from ignorance” or an “anti-God/atheism-of-the-gaps” fallacy. Much of the genome’s function is still unknown, and many supposedly “non-functional” elements are increasingly found to have regulatory or other biological roles. For instance, see my last article on the DDX11L2 “pseudo” gene which operates as a regulatory element including as a secondary promoter.

- If these elements are functional, their homologous locations are easily explained by a common design model, where a designer reuses functional components across different creations.

- The “functionality” of ERVs, for instance, is often downplayed in arguments for common descent, despite their known roles in embryonic development, antiviral defense, and regulation, thereby subtly shifting the goalposts of the argument.

- Probabilities of Gene Duplication and Fusion:

- The probability assigned to beneficial gene duplications and fusions (which are crucial for creating new genetic information and structures) seems inconsistently high when compared to the low probability assigned to the evolution of new codon styles. If random copying errors can create functional whole genes or fusions, then the “impossibility” of a new codon style seems a little arbitrary.

Conclusion:

The overarching argument is that while common descent can certainly explain the observed patterns in biology, its explanatory power often relies on post-hoc rationalization and a flexibility that allows it to account for almost any outcome. This diminishes the distinctiveness and predictive strength of the evidence, leaving it ultimately agnostic when compared to alternative models that can also account for the same observations through different underlying mechanisms.

Leave a comment